The demiurge (Greek demiurgos,[1] “craftsman”[2]) is the being who created the world in Gnosticism. The Gnostics identified him with the god of the Old Testament. The Gnostic scriptures portray him as ignorant, malicious, and utterly inferior to the true God who sent Christ to earth to save humankind from the demiurge’s evil world.

The demiurge is given many names in the Gnostic scriptures, but the three most common ones are Yaldabaoth (also spelled “Ialdabaoth”), Samael, and Saklas. “Saklas” comes from the Aramaic word for “fool,” and “Samael” is Aramaic for “Blind God” or “God of the Blind.”[3] The meaning of “Yaldabaoth” is uncertain. The Gnostic text On the Origin of the World fancifully translates it as “Youth, move over there,” but no word or string of words that sounds like “Yaldabaoth” meant that in any ancient Mediterranean language.[4] “Yaldabaoth” is somewhat close to “child of chaos” in Aramaic, but that’s still a stretch,[5] as is the intuitively plausible suggestion that it could be a condensed form of “Yahweh, Lord of Sabbaths.”[6]

In the Gnostic creation myth, Heaven – which the Gnostics called the “Pleroma,” “Fullness” – was all that existed until a divine entity named Sophia tried to conceive on her own, without the involvement of her heavenly partner or the consent of God. Sophia gave birth to a son that was the product of the rebellious and profane desire that had arisen within her.

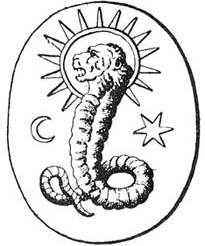

This son of hers was the demiurge. The Gnostic text Reality of the Rulers describes “him” as an androgynous being, an “arrogant beast” that resembled an aborted fetus in both appearance and character.[7] The Secret Book of John adds that he had the body of a snake and the head of a lion, with eyes like lightning bolts.[8] (In ancient Greek philosophy, the lion was frequently a symbol of irrational passions. The Gnostics were steeped in the Greek philosophical tradition, so their description of the demiurge as having a lion’s head was probably intended to show that he was a being who couldn’t or wouldn’t control his base urges.[9] That certainly fits the demiurge’s personality as described in their texts.)

When Sophia saw the horrifying, twisted being that had come from her, she was deeply ashamed and afraid. She disowned him and cast him out of Heaven.

From his lonely position where his madness and conceit could go unchecked, the demiurge gave birth to the archons (“rulers”[10]), beings who were like him and could help him administer the material world. He then created the material world, which, like all creations, was a reflection of the personality of its creator.

The demiurge then created Adam and Eve and imprisoned divine sparks from Heaven within them. He told them that he was the only god and issued the Ten Commandments, even though he himself broke each and every one of those commandments. For example, he lied when he claimed to be the only god and that Adam and Eve would die if they ate the fruit of the Tree of Knowledge of Good and Evil; he insulted his mother and father by refusing to acknowledge their existence; he made a graven image of the divine when he modeled the material world on his corrupt and ignorant misunderstanding of Heaven; and he committed adultery by attempting to rape Eve.[11]

Where the Idea of the Gnostic Demiurge Came From

How could the Gnostics have possibly come up with the idea that such a being created the earth? It seems quite incongruous with Christianity as we understand it today. But in the time when Gnosticism arose (the late first or early second century AD), that wasn’t really the case. To be sure, Jews, Roman pagans, and the Gnostics’ fellow Christians found the Gnostic idea of an evil creator to be shocking and blasphemous. But when we consider the intellectual and spiritual environment within which Gnosticism arose – one that was dominated by Plato’s long shadow, and where Christians were still trying to decide on the basics of their new religion and separate it from Judaism – the Gnostic conception of the demiurge makes a lot more sense.

The word “demiurge” comes from Plato, although Plato’s demiurge was far from evil. For Plato and other pagan Greek and Roman philosophers who followed him, the material world was the creation of a divine “craftsman” who made the world the best reflection of the perfect spiritual world of the Forms that was possible given the constraints of matter.[12]

In Judaism, it was an established tradition to split off particular faculties of God from God himself and credit those lesser divine beings, such as Wisdom, with having assisted God in the creation of the world, as in the eighth chapter of Proverbs and the twenty-fourth chapter of Sirach. Christians inherited and extended this tradition, such as when the first chapter of the Gospel of John identifies Christ with God’s Word/Logos and gives him an indispensable role in creation.[13]

So the Gnostics’ attribution of the act of creation to someone other than the ultimate God was hardly radical by the standards of the Christianity and Judaism of their time – indeed, it was downright conventional. But the Gnostics’ influences all portrayed these divine helpers as benevolent and their work as in harmony with the wishes of the perfectly good ultimate God. How did the Gnostics get the idea that the demiurge was instead malevolent?

Strange as it may at first seem, this, too, was probably a good-faith interpretation of Christian scriptures that were already widespread, popular, and authoritative in the Gnostics’ time. After all, the Gospel of Luke (4:6) and the Gospel of Matthew (4:8) assume that Satan is the ruler of the world when Satan offers Jesus the world in exchange for his worship. Likewise, the Gospel of John mentions an evil “ruler (archon) of this world” in no less than three places (12:31, 14:30, and 16:11). Luke (10:18) and John (12:31) both speak of Satan or a Satan-like entity ruling the earth from the sky and being vanquished by Jesus’s ministry.[14] 1 John 5:19 is even more blunt: “We know that we are God’s children, and that the whole world lies under the power of the evil one.”[15]

The Christians of the first and second centuries, including the Gnostics, were tasked with the monumental project of figuring out what to do with the “Old Testament” that they were supplanting with their own “New Testament.” In the words of Simone Pétrement, they were attempting “to limit the value of the Old Testament within a religion that nevertheless preserves it.”[16]

Early Christians were highly critical of many of the particulars of Judaism, asserting that Christ had come to correct what the Jews had gotten wrong. Consider the Apostle Paul’s remarks to Peter on the Mosaic Law, the centerpiece of Judaism, in Galatians 2:11-21:

We ourselves are Jews by birth and not Gentile sinners; yet we know that a person is justified not by the works of the law but through faith in Jesus Christ. … I have been crucified with Christ; and it is no longer I who live, but it is Christ who lives in me. And the life I now live in the flesh I live by faith in the Son of God, who loved me and gave himself for me. I do not nullify the grace of God; for if justification comes through the law, then Christ died for nothing.[17]

The Gnostics took all of these pieces and combined them. If the world had been created by a lesser being rather than the ultimate God, and if the world was currently ruled by a demonic being, and if Christ had come to correct the flaws of Judaism, why not posit that the Jewish creator god was the demonic being who ruled the world – that Christ came as an emissary from the ultimate God to save humankind from the creator?

Note, by the way, that the Gnostics could arrive at this position even while upholding the sanctity of the Jewish scriptures: everything those books said was accurate, but their authors had been ignorant of the true meaning of what they had written about.[18]

Such a view also had the effect of enabling the Gnostics to make sense of several passages in the Old Testament that had long troubled Christians and even Jews. “The god of Genesis,” notes David Brakke,

walks in an earthly garden and must ask where Adam is (Genesis 3:8-9); he concludes that his creation of humanity and animals was a mistake and decides to destroy all people, except for a single family and a few beasts (6:5-22); and he later annihilates entire cities by raining sulfur and fire down upon them (19:24-25).[19]

The Gnostics took Genesis at its word and concluded that this god was simply malicious, hot-tempered, stupid, and inept.

Archons: Archons were referred to in antiquity as the servants of the Demiurge, the creator god Standing between the human race and a transcendent God that could only be reached through knowledge of humanity’s real nature as divine, leading to the deliverance of the divine spark within humanity from the constraints of earthly existence.

Archon is also Greek word meaning “ruler,” which was also often used in ancient times as the title of a certain public office in a government.

If we take a look at Archons from a Gnostic point of view, we will understand that in this context, they were considered the angels and demons of the old testament.

Hypostasis of the Archons—the divine creators of the universe and humanity

The rulers laid plans and said, “Come, let us create a man that will be soil from the earth.” They modeled their creature as one wholly of the earth. Now the rulers […] body […] they have […] female […] is […] with the face of a beast. They had taken some soil from the earth and modeled their man after their body and after the image of God that had appeared to them in the waters. They said, “Come, let us lay hold of it by means of the form that we have modeled, so that it may see its male counterpart […], and we may seize it with the form that we have modeled” – not understanding the force of God, because of their powerlessness. And he breathed into his face, and the man came to have a soul (and remained) upon the ground many days. But they could not make him arise because of their powerlessness. Like storm winds, they persisted (in blowing), that they might try to capture that image, which had appeared to them in the waters. And they did not know the identity of its power. (Source)

Also called The Reality of the Rulers, the Hypothesis of Archons is an exegesis—a critical interpretation of a religious text—on the Book of Genesis 1–6 and expresses Gnostic mythology of the divine creators of the cosmos and humanity.

Image Credit: Klaus Wittman. Posted with permission.

The Book of Genesis is the first book of the Hebrew Bible (the Tanakh) and the Christian Old Testament.

This ancient text was revered among many other from the Nag Hammadi Library. The Nag Hammadi library also called the “Chenoboskion Manuscripts,” or the “Gnostic Gospels” is a collection of a number of ancient Christian and Gnostic Texts found in Upper Egypt in 1945.

The Reality of the Rulers is believed to have been written sometime during the third century CE. Researchers believe it originated from a traditional period in Gnosticism when it was converting from a purely mythological state into a philosophical phase.

The writing is presented as an instruction on the theme of the dominators (archons) of the world mentioned by St. Paul.

The express intention of this writing is to teach the truth about the powers that have authority over this world.

The story begins with the boast of the demiurge, the supreme archon, in words attributed to the God of the Bible: “I am who I am, God is nothing separated from me.”

The Reality of the Rulers is presented as a learned treatise where a teacher approaches a topic suggested by the dedicatee of the work. The treatise starts off with a fragment of cosmogony, which guides to a revisionistic “true history” of the events in the Genesis creation story, revealing a Gnostic distrust of the material world and the demiurge that conceived it. An “angelic revelation dialogue” emerges within this narrative where an angel repeats and elaborates the author’s fragment of cosmogonic myth in much broader scope, concluding with a historical prophecy of the coming of the savior and the end of days.

Bentley Layton, Professor of Religious Studies (Ancient Christianity) and Professor of Near Eastern Languages and Civilizations (Coptic) at Yale University writes, “The Reality of the Rulers (‘Hypostasis of the Archons’) recounts the gnostic story from the creation of Yaldabaoth down to Noah and the great flood and finalizes with a prediction of the final advent of the savior, the destruction of demonic powers, and the victory of the Gnostics.

As noted by Roger A. Bullard in his book “The Hypostasis of the Archons: The Coptic Text with Translation and Commentary“, the beginning and conclusion to the text are Christian Gnostic, but the remaining of the material is a mythological account about the origin and nature of the archontic powers peopling the skies between Earth and the Ogdoad, and how these ancient events influence the destiny of man.

Although not related at this point, is it possible that the so-called Archons were somehow connected to the Ancient Anunnaki? Food for thought.

According to the Hypostasis of the Archons, these are the Mythic characters:

The Parent of the Entirety: The invisible virgin spirit

Incorruptibility

The Child: Presides over the entirety

The Four Luminaries: Eleleth and three others

The True Human Being

The Undominated Race

Wisdom: Sophia or Pistis Sophia

Zoe (Life): daughter of Sophia

Yaldabaoth: The chief ruler also called Sakla and Samael

Sabaoth: One of Yaldabaoth’s first seven offspring

Adam: The first human being

Eve: Adam’s wife and counterpart

Cain: Eve’s son begotten by the rulers

Abel: Eve’s son begotten by Adam

Seth: a son through god

Norea: Eve’s daughter

References:

[1] Markschies, Christoph. 2003. Gnosis: An Introduction. Translated by John Bowden. T & T Clark. p. 17.

[2] Brakke, David. 2010. The Gnostics: Myth, Ritual, and Diversity in Early Christianity. Harvard University Press. p. 59.

[3] Lewis, Nicola Denzey. 2013. Introduction to “Gnosticism:” Ancient Voices, Christian Worlds. Oxford University Press. p. 137.

[4] Ibid.

[5] Ibid.

[6] Ehrman, Bart. 2003. Lost Christianities: The Battles for Scripture and the Faiths We Never Knew. Oxford University Press. p. 123.

[7] Meyer, Marvin. 2008. “The Nature of the Rulers.” In The Nag Hammadi Scriptures. Edited by Marvin Meyer. HarperOne. p. 196.

[8] Turner, John D., and Marvin Meyer. 2008. “The Secret Book of John.” In The Nag Hammadi Scriptures. Edited by Marvin Meyer. HarperOne. p. 115.

[9] Lewis, Nicola Denzey. 2013. Introduction to “Gnosticism:” Ancient Voices, Christian Worlds. Oxford University Press. p. 137.

[10] Ibid. p. 135.

[11] Ibid. p. 138.

[12] Brakke, David. 2010. The Gnostics: Myth, Ritual, and Diversity in Early Christianity. Harvard University Press. p. 59-61.

[13] Ibid.

[14] Pétrement, Simone. 1990. A Separate God: The Origins and Teachings of Gnosticism. Translated by Carol Harrison. Harper San Francisco. p. 53.

[15] 1 John 5:19, NRSV. https://www.biblegateway.com/passage/?search=1+john+5%3A19&version=NRSVAccessed on 3-18-2018.

[16] Pétrement, Simone. 1990. A Separate God: The Origins and Teachings of Gnosticism. Translated by Carol Harrison. Harper San Francisco. p. 46.

[17] Galatians 2:11-21, NRSV. https://www.biblegateway.com/passage/?search=galatians+2%3A11-21&version=NRSVAccessed on 3-18-2019.

[18] Brakke, David. 2010. The Gnostics: Myth, Ritual, and Diversity in Early Christianity. Harvard University Press. p. 64.

[19] Ibid.

Comments